He made the ground resound with his fall | Pirrin Francis

28 March - 14 April 2012

Kings and Wizards and Dragons; Oh my!

The tale of King Arthur has come about by way of a millennium-and-a-half-long game of Chinese whispers. A combination of folklore and literary intervention, the story has been adapted many times over the course of history. The prevailing tale portrays King Arthur as a British leader of the late 5th and early 6th centuries, who led the defence of Britain against Saxon invaders. Depending on the source, however, he has also been described as a late Roman, a Celt, or a general, or in some cases a guerrilla warrior fighting the Romans, the Picts, or even giants, witches, cat-monsters, divine boars and dragons.

However these stories may vary, each bears a strange disconnect between fact and fiction. As King Arthur is neither an historical figure nor a fictional character, the countless stories written about his conquests play on the boundary between reality and mythology. The legend of the great king was popularised in the 12th century by Geoffrey of Monmouth, with his book, History of the Kings of Britain.[i] The very use of the word ‘history’ in the book’s title implies a factual account of events, however this is a work of fiction, and it is believed the author drew many of his ideas from earlier poetry and literature, and invented the rest. His story presents a number of magical characters whose presence concretes the work as one of fiction. One such character is Merlin the prophet, who has appeared in many Arthurian tales since, such as T.H. White’s well known 1930s book The Sword in the Stone. In White’s story, Merlin (or Merlyn) is a wizard who tutors Arthur during his youth, in order to prepare him for royal life.[ii] Despite these fantastical accounts of Arthur’s life, many historians believe that the character was based on a real historical figure, which further blurs the boundary between fact and fiction in the legend. It is this slippage between the real and the imagined, where Pirrin Francis’ interests lie.

Francis’ recent practice is concerned with how unconventional narrative structures can be used to portray events, places and characters within a realm where reality and imagination overlap. Working predominantly with video and digital media, presented in elaborately staged installations, she deconstructs and disrupts traditional narratives to create an intersection of fact and fiction.

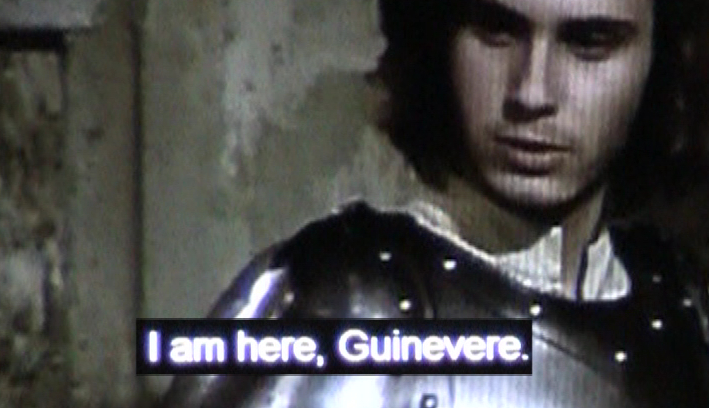

Artwork title aims to reconstruct the Arthurian myth, by drawing on existing material, in much the same way that has been done for the last thousand years. The work takes its inspiration from the 1970s French film Lancelot du Lac (Lancelot of the Lake), known for its use of amateur acting, purposeful lack of emotion in the acting style, and uncharacteristically unglamorous portrayal of the Arthurian myth. With this work, Francis recontextualises the film by editing the footage and interlacing it with sourced video and audio content in order to reconstruct the narrative. While the film focuses on the affair between Guinevere, Arthur’s queen consort, and Lancelot, the most trusted of the knights of the round table, Artwork title reworks the narrative, to concentrate on the relationship between Arthur and Guinevere. Here, Francis re-imagines a conversation between the royal couple, however the fragmented audio and disjointed dialogue cause the narrative to be as elusive and mysterious as the legend itself. The narrative is further distorted by intermittent recordings of different voices, including that of an historian explaining his investigation of the myth, and a poet reading 12th century verse about the king. This layering of different narrative tools serves to acknowledge and complement the inconsistencies and slippages in the many stories of King Arthur throughout history.

While the work makes no attempt to shed light on the opaque Arthurian myth (and in fact, achieves quite the opposite), it does aim to redeem outdated or forgotten narratives about the legendary king. Like in Francis’ earlier works, such as Are they biological 2011which interlaces segments of 19th century film footage with birdcalls, Artwork title combines seemingly disparate video and audio to create densely layered narratives.[iii] By reworking the film footage and interlacing it with distorted recordings poetry recitals, and 6th and 12th century musical compositions (the former being the era when King Arthur is believed to have existed, and the latter being the time that the legend was first widely popularised), Francis breathes new life into each of these tired works. This sense of revival is furthered by the artist’s use of mundane materials. Recycled cardboard, found milk crates, and old tracing paper make up the elaborate structures in Francis’ immersive installations. By deconstructing and reworking these discarded materials, she creates an ethereal setting for the characters in her narrative, and an immersive, bodily experience for the viewer.

What draws Francis to this approach is the chance to interweave cultural and historical narratives with her own stories. The video work concludes with footage the artist took of her cousin playing a fantasy video game in which the main aim is to defeat a dragon god. The inclusion of this footage serves to add a personal dimension to the work. By introducing an autobiographical element, Francis is able to build on the narrative to create new stories. The result for the viewer is a deeply immersive, exceedingly ethereal, and at times disorienting and elusive experience, through which a sense of familiarity prevails.

Katherine Dionysius

Co-director | Current Projects

[i] Carley, J. P. 2001. Glastonbury Abbey and the Arthurian tradition. Cambridge: Boydell & Brewer Ltd.

[ii] White, T. H. 1998 (1938). The sword in the stone. London: Collins.

[iii] Francis, P. Are they biological. Exhibited Brisbane: The Block, QUT. Installation: Video, sound and mixed media (viewed 9 March, 2011).

The tale of King Arthur has come about by way of a millennium-and-a-half-long game of Chinese whispers. A combination of folklore and literary intervention, the story has been adapted many times over the course of history. The prevailing tale portrays King Arthur as a British leader of the late 5th and early 6th centuries, who led the defence of Britain against Saxon invaders. Depending on the source, however, he has also been described as a late Roman, a Celt, or a general, or in some cases a guerrilla warrior fighting the Romans, the Picts, or even giants, witches, cat-monsters, divine boars and dragons.

However these stories may vary, each bears a strange disconnect between fact and fiction. As King Arthur is neither an historical figure nor a fictional character, the countless stories written about his conquests play on the boundary between reality and mythology. The legend of the great king was popularised in the 12th century by Geoffrey of Monmouth, with his book, History of the Kings of Britain.[i] The very use of the word ‘history’ in the book’s title implies a factual account of events, however this is a work of fiction, and it is believed the author drew many of his ideas from earlier poetry and literature, and invented the rest. His story presents a number of magical characters whose presence concretes the work as one of fiction. One such character is Merlin the prophet, who has appeared in many Arthurian tales since, such as T.H. White’s well known 1930s book The Sword in the Stone. In White’s story, Merlin (or Merlyn) is a wizard who tutors Arthur during his youth, in order to prepare him for royal life.[ii] Despite these fantastical accounts of Arthur’s life, many historians believe that the character was based on a real historical figure, which further blurs the boundary between fact and fiction in the legend. It is this slippage between the real and the imagined, where Pirrin Francis’ interests lie.

Francis’ recent practice is concerned with how unconventional narrative structures can be used to portray events, places and characters within a realm where reality and imagination overlap. Working predominantly with video and digital media, presented in elaborately staged installations, she deconstructs and disrupts traditional narratives to create an intersection of fact and fiction.

Artwork title aims to reconstruct the Arthurian myth, by drawing on existing material, in much the same way that has been done for the last thousand years. The work takes its inspiration from the 1970s French film Lancelot du Lac (Lancelot of the Lake), known for its use of amateur acting, purposeful lack of emotion in the acting style, and uncharacteristically unglamorous portrayal of the Arthurian myth. With this work, Francis recontextualises the film by editing the footage and interlacing it with sourced video and audio content in order to reconstruct the narrative. While the film focuses on the affair between Guinevere, Arthur’s queen consort, and Lancelot, the most trusted of the knights of the round table, Artwork title reworks the narrative, to concentrate on the relationship between Arthur and Guinevere. Here, Francis re-imagines a conversation between the royal couple, however the fragmented audio and disjointed dialogue cause the narrative to be as elusive and mysterious as the legend itself. The narrative is further distorted by intermittent recordings of different voices, including that of an historian explaining his investigation of the myth, and a poet reading 12th century verse about the king. This layering of different narrative tools serves to acknowledge and complement the inconsistencies and slippages in the many stories of King Arthur throughout history.

While the work makes no attempt to shed light on the opaque Arthurian myth (and in fact, achieves quite the opposite), it does aim to redeem outdated or forgotten narratives about the legendary king. Like in Francis’ earlier works, such as Are they biological 2011which interlaces segments of 19th century film footage with birdcalls, Artwork title combines seemingly disparate video and audio to create densely layered narratives.[iii] By reworking the film footage and interlacing it with distorted recordings poetry recitals, and 6th and 12th century musical compositions (the former being the era when King Arthur is believed to have existed, and the latter being the time that the legend was first widely popularised), Francis breathes new life into each of these tired works. This sense of revival is furthered by the artist’s use of mundane materials. Recycled cardboard, found milk crates, and old tracing paper make up the elaborate structures in Francis’ immersive installations. By deconstructing and reworking these discarded materials, she creates an ethereal setting for the characters in her narrative, and an immersive, bodily experience for the viewer.

What draws Francis to this approach is the chance to interweave cultural and historical narratives with her own stories. The video work concludes with footage the artist took of her cousin playing a fantasy video game in which the main aim is to defeat a dragon god. The inclusion of this footage serves to add a personal dimension to the work. By introducing an autobiographical element, Francis is able to build on the narrative to create new stories. The result for the viewer is a deeply immersive, exceedingly ethereal, and at times disorienting and elusive experience, through which a sense of familiarity prevails.

Katherine Dionysius

Co-director | Current Projects

[i] Carley, J. P. 2001. Glastonbury Abbey and the Arthurian tradition. Cambridge: Boydell & Brewer Ltd.

[ii] White, T. H. 1998 (1938). The sword in the stone. London: Collins.

[iii] Francis, P. Are they biological. Exhibited Brisbane: The Block, QUT. Installation: Video, sound and mixed media (viewed 9 March, 2011).